Published: Center for Syncretic Studies. .

Published: Center for Syncretic Studies. .

Дмитрий Муза

Dmitry Muza – translated by Jafe Arnold

Dmitry Evgenyevich Muza is a doctor of philosophical sciences, a correspondent-member of the Crimean Academy of Sciences, a professor at the Department of Sociology at Donetsk State University of Management, a professor at the Department of International Relations and Foreign Policy at Donetsk National University, and the co-chairman of the Izborsk Club of Novorossiya (Donetsk People’s.

By including the processes and event-related phenomenon “Russian Spring,” “war,” and “statecraft” in the title of this article, I am by no means implying any kind of intellectual provocation or attempting to realize a political order. On the contrary, the intended position here can be associated with the existence of millions of people who have in one way or another engaged (during wartime) in the creation of a completely distinct region, a will and fate of more than just one century tied to the fate of the Russian world.

Proposed below is a feasible analysis of three interrelated events: the “Russian Spring” in Donbass, the war [1], and attempts at state-building, each of which deserves separate reflection and evaluation from the position of both an “internal” and “external” observation.

All of these factors, I believe, are tied to an immanent logic which can be articulated as a centripetal process of reintegrating Donbass into the Russian civilizational, i.e., Russian-Eurasian, Orthodox space.[2]

In addition, a general exposition of what is happening in Donbass and with Donbass today requires some clarification of the region’s pre-crisis state. Such a clarification concerns both the recent and distant past directly associated with the region under consideration. By going through these layers of history, I intend to show the composition of Donbass in relation to the larger Russian civilizational space.

First of all, it is necessary to recall that the now forgotten regional referendum of March 27th, 1995 in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions was intended to restore socio-economic ties with the Russian Federation and enshrine the Russian language as a regional one in functional norms. Of no small importance is that this referendum was consistent with the Ukrainian law “On all-Ukrainian and local referendums,” but was still ignored by Ukrainian authorities. Secondly, it was Russian Donbass that accounted for the electoral base of Presidents Kuchma and Yanukovych who flirted with the ideas of closer integration with Russia and the Russian language (granting it a special status). Thirdly, there were considerable expectations surrounding the post-Maidan congress in Northern Donetsk in November of 2004 which expressed the region’s collective will on establishing genuine federalization, including economic autonomy for the Donetsk and Lugansk regions. Fourthly, it is important to emphasize that the significance of the recent “Euroregion Donbass” project which involved the Rostov, Belgorod, and Voronezh regions from Russia and the Donetsk and Lugansk provinces from Ukraine entailed tightening their cooperation, albeit with European investments and guidance.

Second of all, it is only natural that the young Donetsk People’s Republic, having directly declared its continuity with the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic [3] up to the point of inheriting flags and other attributes of statehood, is linked to the development of this referential phenomenon [4]. In passing, let us note that the republic’s founding fathers counted it as part of the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic in writing.

“Donetsk Federative Republic” – an alternative documented name for the DKR

The connoisseur of the DKR’s history, the historian and political scientist Vladimir Kornilov, rightly remarks:”In practically all of the founding documents on establishing the DKR, an inextricable link to Russia is emphasized. This is the ‘red thread’ running through all the appeals and requests of the DKR’s various organs. Meanwhile, the declaration signed by Artem on the future activities of the Sovnarkom of the Republic (February, 1918) determined the following task to be essential: ‘Strengthening the power of the Workers and Peasants’ Government of Russia; active participation in socialist construction which inevitably leads to deepening the revolution; and realizing the regulations, decrees, and orders of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Federative Socialist Republic of Soviets in Russia.’”[5]

It is of more than a little interest that the founders of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic (F. Artem “Sergeev”, V. Mezhlauk, V. Filov, M. Zhukov, K. Voroshilov, F. Kon, etc.) were not ethnic Ukrainians [6]. En masse, they were Russians who were predisposed not only towards the great space, but the Homeland itself!

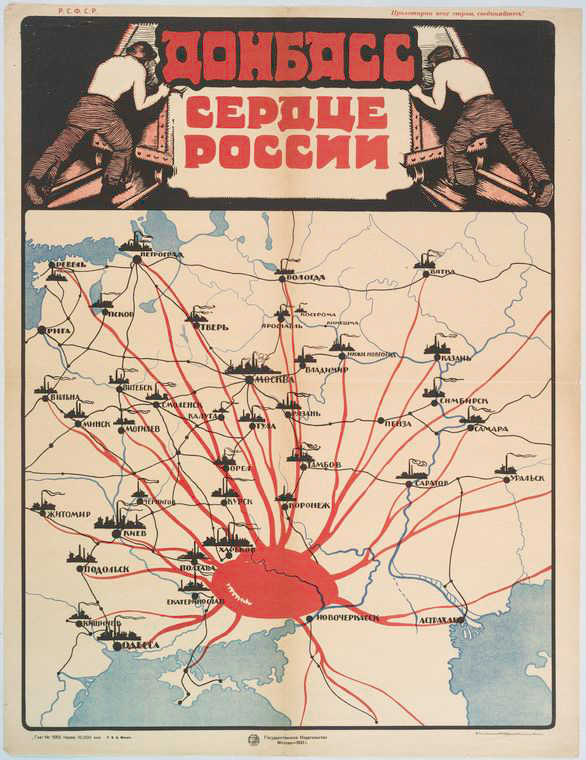

In addition, the artistic generalization made in the early 1920’s is crucial. This concerns the famous poster:

“Donbass – the heart of Russia”

As follows, even at first glance this portrayal of Donbass presents its essence as as land of labor which guarantees the “bread of industry” for the European part of Russia. In this regard, the observations of V. Kornilov are of interest: “Now the slogan ‘Donbass – the heart of Russia’ and the relevant poster from 1921 might surprise someone. But then, in the early 1920’s, this slogan did not surprise Donbass natives or the inhabitants of Russia. Even though they spoke about the fight for Soviet Ukraine, they were fighting for Donbass and, in doing so, quite clearly engaged the task of merging it with the all-Russian state, no matter which republic it was conjoined to.” And the most important point here is that of self-identification: “The residents of Donbass themselves, despite that they had lived up until the 1920’s in various state and quasi-state entities, continued to consider themselves Russians, having in mind, of course, not so much ethnic belonging as state belonging.”[7]

Here it is important to mention the territorial disputes surrounding Donbass (1920-1925) which unfolded following the “liquidation” of the DKR and its “free” industrial agglomeration with Soviet Ukraine. According to Gosplan’s original draft, South-West Russia was supposed to be divided into three regions: the Caucasus, with its center in Vladikavkaz, the Southern-Mountain-Mining region with its center in Kharkov (including the entire Donets basin plus the Western part of Donetsk region with Rostov-on-Don), and the Lower Volga region with its center in Saratov (including the Eastern part of the Don region) [8]. But later, thanks to the efforts of Ukrainian communists starting with the II Congress of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) in Moscow from October 17th-22nd, 1918, Donetsk-Krivoy Rog was put into question and then, thanks to the personal bureaucratic intrigues of N.A. Skrypnik [9], was finally, but not irrevocably, conjoined to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic! Of course, this was contrary to the will of both the founding fathers of the DPR, first and foremost Artem (Sergeev), and the population of the Donetsk region.

A long time has passed since then, and developments in the USSR and post-Soviet Ukraine evolved rapidly. The country found itself on the verge of the first, and then second Maidan.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning the “revelations” of the political scientist and adviser to several Ukrainian presidents, Dmitry Vydrin. A very curious formula for diving Ukraine into zones occurred to him. Examining the country in terms of psychological heterogeneity, he postulated that the country’s structure featured the presence of two dominant sub-psychological zones, the Eastern Ukrainian and Western Ukrainian ones, along with three varying bi-psychological zones: Dnepropetrovsk, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia.

Developing his fanciful construct, Vydrin assertively claimed that Eastern Ukraine had its own sacred capital, Donetsk, and that the bearers of its according mentality were “Janissaries.” The latter was constructed by analogy to the famous Turkish warriors “who were well versed in offensive technique, were desperate and reckless invaders – like our ‘raiders’ – but always fiercely defended their own territory.”[10] In addition, “they almost never created their own fortresses, believing that their credo was seizing others’ fortress and not building their own.” The Kiev guru, however, falls into an (insoluble) contradiction, namely, he claims that these very “Janissaries” “for all their lives, largely remained citizens and patriots of their native towns and villages.” [11]

This means that, on the one hand, the “Janissaries” “did not create” and yet “fiercely defended” their own fortresses while, on the other, they were “citizens and patriots” of their towns and cities. The anecdotic nature of this analysis can be explained in different ways, such as, for example, by pointing to the fact that Vydrin tactlessly labeled both the Donetsk oligarchy and the ordinary people of Donbass with the term “Janissaries”, or by recalling that the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ elite are called “cyborgs” (and also “hiders”) who en masse represented this or that region of “independent” Ukraine, i.e., the Lvov region. But here we are reminded of the late Oles Buzina, the archetype of hapless historians and writers who experiment with the Russian people (its southern segment) in trying to cram the people itself and their existence into an artificial and stillborn construct. Quote: “The pagan chimera originating in the hearts of a small group of intellectuals suffering from an inferiority complex demands a new batch of victims in order to realize their reality. After all, each of their souls creates only its ‘own’, ‘personal’ Ukraine!”[12]

But let us return to the main subject.

Staring truth in the face, it must be emphasized that relations between Eastern Ukraine and the new, independent (from Moscow) Ukraine have become entirely dialectical. The reason for such is the systematic betrayal by the local elites who categorically desired not to fall out of the vertical of power. It is characteristic that these elites had a dual identity. On the central level, the elites saw themselves as a parliamentary opposition (and, in the case of victory, the parliamentary majority), while on the regional level they were feudal princes whose power could never be challenged by anyone.

Even the Orange Revolution did not alter their status or situation. On the contrary, in one way or another they managed to bargain with the “triumphant Maidan” over a piece of parliament, privileges, and the inviolability of “their” businesses on territories controlled by them. Eastern Ukraine’s public sentiments were often seen as a mere object up for bargaining with Kiev.

It is thought that it is precisely from here that stems the reluctance and inability of the elites to take legitimate decisions at the level of regional councils immediately following the coup d’etat, when the desired format of Novorossiya (with at least 7 provinces) could have been put forth, leaving Kiev with a tough choice – either splitting Ukraine or immediately transitioning from the unitary model of state to a federative one.

On the contrary, varying public sentiments only grew in the thick of the masses of the people of Donbass and the organizations and movements which stood behind such – the Donbass Inter-Movement (1989-present), the Donetsk Republic (2005-present), the “Russian Bloc” which ran in local elections more than once, the “Russian March” on each November 4th which emerged in 2005, and the Russian Center which had actively operated since 2009 at the Krupskaya Regional Universal Scientific Library in Donetsk. In fact, these forces became the basis for the “Russian Spring” which gathered 40,000 people out to a rally on March 1st, 2014. Some consider this rally to have given rise to a real “revolution of dignity.”

“Revolution of dignity” – Russian Spring supporters protesting against the Maidan in Zaporozhya stand as they are pelted with eggs, trash, and stones by Ukrainian nationalists, thus yielding the famous scene “300 Zaporozhyans”

The course of the Russian Spring was, nonetheless, dramatic. The first stage took place under several slogans, such as “Crimea, Donbass, Russia!”, “Down with the junta!”, “Donbass is Russian!”, and “Donbass is no place for corrupt oligarchs!”, etc. But at one point, it became clear that the Crimean scenario could not be realized given the legitimate Donbass government’s lack of decision-making. Nevertheless, in April 2014, public representatives of the Donetsk and Lugansk regions declared the DPR and LPR and scheduled popular referendums on the Act of State Independence of the Republics. The Declaration of State Sovereignty of Novorossiya and the agreement on establishing a Union of Sovereign Republics of Novorossiya also appeared. The status of the documents was accepted by a congress of deputies from all levels of the DPR and LPR on December 12th, 2014.

Following the announcement of the May referendum’s results, projects appeared for formulating constitutions for the Donetsk and Lugansk people’s republics (later amended), which provided for the possibility of conjoining the DPR and LPR into a “federative state” with rights for the federation’s individual subjects. The territory of the republics was defined as the borders of the Donetsk and Lugansk provinces, two-thirds of which were under the control of the republics at that time.

The ideological article in the Constitution repeated the Yeltsin Constitution, and therefore did not offer any clear guidance for state construction. Only much later in fall of 2016, on the initiative of DPR head A.V. Zakharchenko, did discussions on the ideological construct of “USSR – Freedom, Conscience, Justice, and Equality” begin which set the course towards a social state and defined the republic’s belonging to the larger “Russian World.” Although this correction still did not provide a complete understand of what exactly is to be built on the land of Donbass, one thing was clear: Donbass would not be built like the “new” Ukraine, driven by hatred towards Russia and Russians. The Donbass that remembers and honors Izotov, Vatutin, Angelin, Father Zosim (Sokur), Prokofiev, and Kobzon, has no room for such.

Even today, there is no certainty as to how the republics will resolve issues of citizenship, property (in the LPR, for example, under the Constitution, the land belongs to the people, but in the DPR the right to private ownership of land can belong to citizens and their associations), social protection (both the DPR and LPR’s constitutions declare themselves to be social states), the continuity of government, or, finally, their territorial borders, just as there is little clarity in light of the Minsk Agreements (extended to 2016) and the Kiev regime’s failure to implement them.

The Kiev regime has drawn itself into a hybrid war involving private military corporations from 39 countries wanting to “liberate” these territories from vatniks and colorados [13] who dared to oppose the Poroshenko-Turchynov-Yatsenyuk clique. For the new Ukraine which is destroying its own legal foundations, the Minsk Agreements are largely a dead end. Any changes in legislation – the value of which would be zeroed out anyway by the coup and subsequent unconstitutional (!) use of the armed forces and other military formations for restricting the rights and freedom of citizens – represent a direct threat to “independent” Ukraine.

What’s more, Kiev sees the largest threat of all in the presence of Russian troops in Donbass, which is apparently so active that this alone prevents the regime from carrying out full-fledged genocide against the rebellious population and driving it into special concentration camps such as the one in Talakovka.

But here one can produce a legitimate argument from a poetic revelation, namely, the poetess Yunna Moritz’s stanzas in response to accusations that Russia has “occupied” Donbass:

THERE ARE NO RUSSIAN TROOPS ON MARS

There are no Russian troops in Donbass

But there is much Russian character

No wonder these traits are called troops!…

(НА МАРСЕ НЕТ РОССИЙСКИХ ВОЙСК

В Донбассе нет российских войск,

Но много есть российских свойств, –

Не зря войсками называют эти свойства!…)

Footnotes

[1] I note in passing that in the minds and lips of some, the war is treated as a civil war (D. Gau, P. Rasta), while for others it is ideological (Dz. Keza), a network war (V. Karolin) or network-centric war (A. Dugin), a geopolitical war (L. Ivashov), a “psycho-historical” war (A. Fursov), or, for others, a “hybrid” war (S. Markov). It appears that the wide range of definitions itself testifies to the supreme complexity of this phenomenon which is still far from its conclusion and, as follows, still far from a common conceptual denominator. Nevertheless, the war’s interpretation as a hybrid one is the most likely insofar as it allows one to integrate different aspects of events (the second “Maidan” and coup in Ukraine as moments of the destruction of Russia’s policy, the genocide of Russians and Russian speakers in Donbass, the participation of PMC’s in the conflict, sanctions, the the game surrounding oil prices, the information war, etc.) and interpret them by focusing on the geostrategic perspective of the US’s envisioned final elimination of Russia from the “Eurasian chessboard.”

[2] See D.E. Muza’s Krym-Donbass-Rossiya: o faktorakh formalno/neformalnogo prityazheniya v kontekste Russkoy vesny in Novaya Zemlya, March 2015, No. 2 (5), pp 43-46.

[3] See the “Memorandum of the Donetsk People’s Republic on Principles of State-Building and Political and History Continuity” adopted by the National Council of the DPR and signed by its chairman, A.E. Purgin, on June 2nd, 2015.

[4] The establishment of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic was proclaimed ay the 4th Congress of Soviets of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog basin on February 12th, 1918.

[5] Kornilov, V.V. Donetsko-Krivorozhskaya respublika. Kharkov: Folio, 2011, pp 167.

[6] Ocherki istorii Ukrainy. Under the general editorship of P.P. Tolochko. K.: Kievskaya Rus’, 2010, pp. 326.

[7] Kornilov, V.V. Donetsko-Krivorozhskaya respublika. Kharkov: Folio, 2011, pp 519.

[8] See Y.I. Galkin, Sbornik dokumentov o pogranichnom spore mezhdu Rossiey i Ukrainoy v 1920-1927 godakh za Taganrogsko-Shakhtinskuyu territoriyu Donskoy oblasti (supplement to the journal Novaya Zemlya by the Izborsky Club of Novorossiya, Donetsk: Izborsky Club of Novorossiya, 2015, pp. 5.

[9] He convinced Lenin and Stalin

[10] Vydrin, D.I., O politick bessporno, K.:Sammit-Kniga, 2011, pp. 44.

[11] Ibid, 47.

[12] Buzin, O., Soyuz plus i trezuba: Kak pridumali Ukrainu, L.:Arius, 2013, p. 489.

[13] Translator’s note – “vatniks”, referring to the jackets typical of the Donbass working classes and elderly, is used by Ukrainians in a derogatory sense implying the “poverty” and “dirtiness” of Donbass natives. “Colorados” is another Ukrainian “insult” likening the colors of the St. George Ribbon that came to symbolize the anti-Maidan and Russian Spring movement to the colors of a local beetle, thus implying that anti-Maidaners are “insects.”

Copyright © Center for Syncretic Studies 2016 – All Rights Reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced for commercial purposes without expressed consent of the author. Contact our Press Center to inquire. For non commercial purposes: Back-links and complete reproductions are hereby permitted with author’s name and CSS website name appearing clearly on the page where the reproduced material is published. Quotes and snippets are permissible insofar as they do not alter the meaning of the original work, as determined by the work’s original author.